Before I start, I must first acknowledge the Tangata Whenua of Aotearoa and, second, their unceded sovereignty over their whenua. Alofa and much respect ❤

'We have a right to our imagined traditions, to our imagined places, and those traditions and places are most powerful when we confess they are imagined.' - Ta-Nehisi Coates (from his book 'The Message').

Many of us born and raised outside Samoa have lived our ideal Samoan life through our parents' dreams. We grew up on the memories of villages, aiga, and communities they shared with us, but the reality for some (I mean me) was that there is no ideal when you rely on what is essentially a 'best of' playlist of their melancholy. Those are their memories, loves and losses.

Imagine living on land that your aiga has had ties to for generations, and the privilege of that connection is that the ele'ele (dirt) has your DNA buried deep within it (quite literally when you see some have their loved ones buried right by the front of homes). Everything you know, everyone you know and all your memories are tied to the alofa of this place - and then you are told to leave. You must break these ties and become responsible for returning remittances to support your aiga. You do so because that is what our people do: they tautua and sacrifice for the good of all. That is the legacy they built.

I call out the idea of some of them coming for a better life for my generation; we existed only in the potential of connections they made when they sought the comfort of those familiar in unfamiliar lands. For some, the protocols of honouring the hosts of this land would mean a misfired allegiance to the attitudes of Palagi and their racist attitudes towards our cousins, who are the true guardians of Aotearoa. I have also become painfully aware that for the longest time, I believed my generation of Gen X Aotearoan-grown Samoans were the first to suffer through an identity crisis and the tyranny of multicultural confusion. Only after I finally calmed my fiapoko ears and eyes, did I see the 'struggle and endure' attitude of our parents' silent generation. We grew up with options for the way we slipped words from our mouths; we learned to code-switch early on as a way to find acceptance and, in my shame, pull away from the generation we called 'fresh'.

In our lifetimes, we have seen the hosts we hugged turn on us and come banging on our doors, looking to eject us from the lands they stole from our cousins. We would be seen as fit for screen and field but far from ideal for management or corporate ladders. The idea of generational wealth was not our parents' dream. They were the cultural wealth we needed to treasure, and now, for some, they only come to us in our dreams.

My first trip to Samoa in 1998 was not the open-armed, frangipani-scented hug I had imagined; it was a cold shove to dispel my daydreaming of a Palagi world and a re-introduction into the responsibility of becoming Samoan. My second time in Samoa was in 2016; however, that was where I found my parents. Samoa showed me what they left behind, why they loved her and kept parts of her alive so stubbornly. They would never come home to her but I could at least give part of what was them, in me, back.

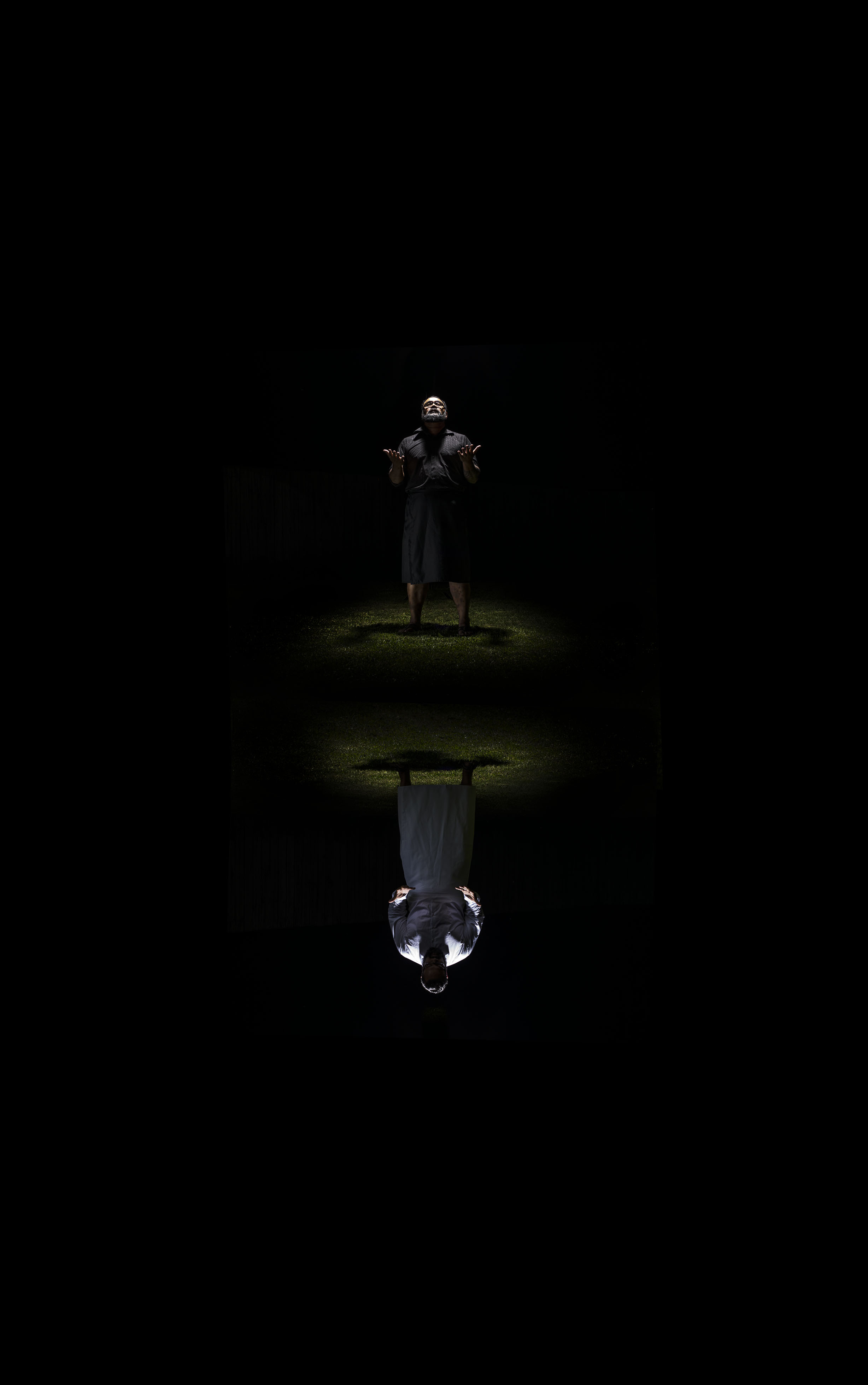

Time and our own melancholy remind us of what has been, what has been sacrificed and, hardest of all, what is being lost.

I am not the same Samoan as my parents, nor am I the same Samoan as the generation that has come after me. My generation will be responsible for keeping the reality of our parents' generation alive. How do we do that? If I'm being honest, I'm still working it out.

In the meantime I will try to find a lyricism in science fiction, the rhythms of tar sealed roads that connect my concrete sea of islands in my suburb of Manurewa (thanks @natalie roberston). A Samoan in a space helmet looking for acceptance.